- Home

- Lisa Shanahan

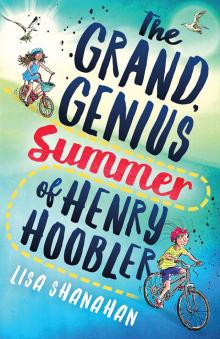

The Grand, Genius Summer of Henry Hoobler

The Grand, Genius Summer of Henry Hoobler Read online

OTHER BOOKS BY LISA SHANAHAN

For older readers

My Big Birkett

For younger readers

Sweetie May, illustrated by Kerry Millard

Sweetie May Overboard, illustrated by Kerry Millard

Picture books

The Whole Caboodle, illustrated by Leila Rudge

Big Pet Day, illustrated by Gus Gordon

Daisy and the Puppy, illustrated by Sara Acton

Bear and Chook by the Sea, illustrated by Emma Quay

Bear and Chook, illustrated by Emma Quay

Sleep Tight, My Honey, illustrated by Wayne Harris

The Postman’s Dog, illustrated by Wayne Harris

Daddy’s Having a Horse, illustrated by Emma Quay

My Mum Tarzan, illustrated by Bettina Guthridge

Gordon’s Got a Snookie, illustrated by Wayne Harris

What Rot! illustrated by Eric Löbbecke

First published by Allen & Unwin in 2017

Copyright © Text, Lisa Shanahan 2017

Copyright © Illustrations, Judy Watson 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

A Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 9781760293017

eISBN 9781952535994

Teachers’ notes available at allenandunwin.com

Cover and text design by Debra Billson

Cover illustrations by Judy Watson

For Rohan

CONTENTS

Leaving

Arriving

The Right Sort of Courage

The Very Worst Thing

A Knight on a Shining Bike

Treasure

Genius

Surprises

Making Plans

World Cup Cricket

Lost

Found

A Bright, Loud Life

The Grand, Genius Summer

Straight-up and True

Magic

At Home in the World

Well and Truly Made

A Huge, Heaped Plate

Beginnings and Endings

LEAVING

It was nearly time to go.

Henry tweaked the blind and peered out the window. The car was at the top of the drive. The trailer was locked on. It was bulging with the tent, tarp poles, sleeping-bags, mattresses, torches, tables, chairs, boogie boards, fishing rods and every sort of ball in the universe, including totem tennis. And there was his new silver bike, hitched to the back, the front wheel whizzing.

Henry dropped the blind. He slid down between the wall and the bed. He held his breath. If he was very quiet, they might leave without him. Maybe they wouldn’t even notice he wasn’t there. Then he could stay at home alone and live on tinned tuna and crackers and baked beans and never have to worry a single moment about bugs, spiders, snakes, stingers, blue-ringed octopi, tsunamis, sharks and a new silver bike without training wheels.

‘Heno?’ Dad called. ‘Are you set? Are you ready? Everyone’s waiting.’

If he stayed very still and they left without him, he could sleep in his bed for the whole holiday instead of on the ground, and he wouldn’t have to travel for hours and hours in the car, stuck in the middle between Patch and Lulu. His big brother Patch, who didn’t talk much anymore and never wanted to play Minecraft or Monopoly or dodgeball on the trampoline, but only listen to music on his phone and joggle his leg nonstop, maybe for fifteen hours straight, maybe enough to get into the Guinness Book of Records. And his younger sister Lulu, who only ever wanted to play dumb ponies and speak horse!

‘Hey there!’

Henry’s doona flew up. All the dark and warm and the smell of boy and scruffy dog went with it.

Dad bent over. ‘What are you doing down there, Heno?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Are you stuck?’

‘No.’

‘Well, it’s time to go, mate,’ said Dad, flicking the doona back. ‘We want to hit the road before the traffic gets too bad.’

‘Maybe you could go without me?’

Dad raised an eyebrow. ‘What?’

‘Mrs Neale from next door could check up on me, like she does on Charlie Olson’s cat.’

‘Aaah, Heno, you’re a little more work than a cat, mate.’

‘What about Nonna?’

‘She’s looking after Beatle! And he’s not the sort of dog to sit on her lap. He’s going to take up all her energy and time.’

Henry knew this was true. Their dog Beatle was lovable and adorable and full of goodwill – licks and love – but he never did sit still. He was all fetch and drop and go and play, from the second he woke up till the second he went to bed, and even then his four legs still raced in his dreams.

‘Look, Heno, you’re going to love it! We’re right on the water. There’s a bike path bang outside the tent. There’ll be scootering, skateboarding, fishing and swimming. Everyone is going to be there. The Carsons and the Barones. It’ll be fun! Like Friday night tennis, only every day.’

Henry shrugged. The Hooblers, the Carsons and the Barones had played tennis on Friday nights for a long time, ever since Patch, Dylan and Jay became close friends in kindy. But Friday night tennis was not quite as much fun lately. Patch, Dylan and Jay mostly played tennis with the adults now, because they were nearly fifteen and knew how to serve and could hit the ball over the net, more often than not. No one ever wanted to play tag or hide-and-seek or spotlight anymore. Carey spent the whole time sitting sideways in the umpire chair, reading comics, while Reed bossed Henry, Lulu and Kale around the kids’ court.

‘Look,’ said Dad. ‘There’s a bunch of brilliant stuff to do down there. You’ll be able to go yabbying on the sandflats and see the soldier crabs marching out like a tiny blue army. And the stingrays down by the wharf, if we’re lucky!’ He leant his knee on the bed. ‘It’ll be paradise! Yelonga is my favourite place in the world. The place I camped with my family when I was a boy like you.’

Stingrays! Holy Kamoley! No one had mentioned stingrays before. What if Henry fell off the wharf and landed on top of one and it carried him out into the deep and he slipped off and ended up being swallowed by a whale shark?

‘At night, we’ll play board games and cards, sizzle some sausages and watch the sky light up with stars.’

Board games and cards! Henry played his Nonna every Thursday afternoon, when Patch was at soccer and Lulu was at dancing. And not just baby games like Snakes and Ladders. He was always smashing his Nonna at Monopoly and Cluedo and Up the River, Down the River, and it wasn’t because she was going easy on him, either.

Dad grinned. ‘And you know what, Heno, there’ll be gelato! Gelato like you’ve never tasted. Every flavour under the sun. They make it from scratch! How about I personally promise you bucketloads of gelato?’

Gelato! Henry liked that too, even better than plain ordinary ice-cream. And bucketloads of flavours! The prospect sent a sparkle right up through the roof of his mouth.

‘That’s a big promise,’ he said, gazing at the ceiling. He didn’t want to appear too eager. There was the problem of his bike, after all, and still the possibility of bugs, spiders, snakes, stingers, blue-ringed octopi, tsunamis, sharks and stingrays and now maybe even whale sharks too.

‘I’m confident I can deliver a mountain of gelato,’ said Dad. ‘Easy-peasy.’

Henry sniffed. ‘All right, then,’ he said, and he held out his hand so his dad could drag him from his hidey-hole.

It took ages to get out of the city.

‘Everyone is going on holidays,’ cried Lulu. She stared out at the cars, glittery and shiny, stopping and starting beside them.

‘Ye-es,’ said Dad. He drummed his fingers on the steering wheel.

Mum unwrapped another barley sugar. ‘Everyone had the same good idea.’

‘That’s for sure,’ said Dad, with a deep, deep sigh.

‘Spotto!’ Lulu tapped her pony against the window. ‘Neigh! Marigold is winning. She just saw another yellow car.’

‘How many yellow cars now?’ asked Mum.

‘Ten,’ said Lulu.

‘Good counting,’ said Mum. ‘See! You are ready for big school. Only a few more weeks now.’

‘I don’t want to talk about that,’ said Lulu, folding her arms. ‘I already told you.’

‘Alright then,’ said Mum. ‘My lips are zipped. How many purple cars have you spotted?’

‘Only two,’ said Lulu. ‘Poor Violet is getting grumpy.’

‘Mmm,’ said Mum. ‘I don’t think purple is the most popular colour.’

‘There are more pink cars,’ said Lulu. ‘So Peony is happy. Very happy!’

Henry wriggled. ‘How much longer?’ he asked.

‘Five and a half hours,’ said Dad.

‘Holy Shamoley,’ breathed Henry.

‘Five and a half hours! But you already said that before, when we just left home,’ said Lulu.

‘Ha!’ said Dad. ‘It’s always five and half hours, no matter when you ask. Even when we’re just five minutes away.’

‘In other words, it’s a long, long time yet,’ said Mum. ‘And you might as well have a rest, if you can.’

‘But I’m not tired,’ said Lulu, dancing her yellow pony along the windowsill.

But within five minutes she was fast asleep, her head nodding, her hair clinging to her sweaty forehead, her hot bare foot resting on Henry’s knee. Smelly ponies avalanched out of her lap, sending up a sweet waft of strawberry, apple and musk.

Henry lifted Lulu’s foot gently and placed it back near her booster seat. The problem with being in the middle was there was always someone on either side taking up just a bit extra, inching their way into his space. Henry shuffled across the seat away from Lulu and her ponies, accidentally nudging Patch, who grunted and flinched. ‘Watch it!’ he growled, opening his eyes to glare at Henry. Gosh, Patch was like some kind of pimply, snappy, carnivorous Venus flytrap!

A lump rose in Henry’s throat. He slid his leg back and gazed out the front windscreen, at the vans and the station wagons and the four-wheel drives pulling caravans and trailers and boats slowly forwards, at a whole city out on the road, moving house for just a few weeks, pillows puffed up in rear windows like fat clouds.

‘I didn’t like going on holidays when I was young.’ Mum folded a crinkly clear barley sugar wrapper into a tiny square.

Henry stretched forward. ‘What?’ he said.

‘I didn’t like going on holidays when I was little.’

‘How come?’

‘I don’t know,’ said Mum, sliding the wrapper into a plastic-bag bin. ‘Maybe some people are more homebodies at heart.’

Was Henry a homebody at heart? He wasn’t sure. Perhaps he hadn’t gone away enough to know yet. Staying with Grandpa and Grandma Hoobler probably wouldn’t count as a real holiday, even though it was by the sea, because they’d been going there since he was a baby so it still felt like home. He didn’t want to think about their last family camping trip. On a farm, by a river. The cows. The poo. The flies. The mud. The chickens. The hissing geese that kept popping up like horrible cartoon characters, when he least expected them. What if you were born a homebody? Did you stay that way forever?

‘I love holidays,’ said Dad, glancing over his shoulder. ‘All the adventure and promise of new things to see and do! No clocks or timetables or places to be. Waking up and going to sleep with the sun. Alive to the wind and the sound of the sea. Aaaaah, so much opportunity! Kitesurfing and standup paddleboard riding, swimming, making castles and digging huge holes, skateboarding and jumping off the wharf. A plethora of pleasures.’

‘Hmmm,’ said Mum. ‘Not everyone feels the same way.’

‘I know,’ said Dad. ‘That’s true.’

‘When I was young and we were going on holidays, I always had this feeling just as we were about to leave,’ said Mum. ‘I couldn’t quite put my finger on it back then, but looking back now, I think it might have been dread.’

‘Dread?’ said Dad. ‘Really? What’s to dread about an old holiday?’

‘You know,’ said Mum. ‘What if something happened?’

Dad fiddled with his headrest. ‘Well, you’d hope so! You’d want something to happen. No one loves a nothing sort of holiday.’

‘But maybe something bad!’

Dad shook his head. ‘Something bad? Geez.’

‘Did something bad ever happen?’ asked Henry.

‘Well, no. Nothing exceptionally bad,’ said Mum. ‘Just the usual kinds of bad like fighting with my sisters, getting sunburnt and dumped by a big wave, dropping an ice-cream cone on the footpath before I’d even taken a lick. But even so, every time I went away, I just had this nagging worry in my chest, like a moth buzzing up against a bright porch light, that something terrible might happen.’

Henry nodded. He knew about that moth.

It was fluttering in his chest even now. ‘Do you still get that worry?’ he asked.

‘Sometimes, yes,’ said Mum, nodding. ‘Yes. I do. It’s a lot smaller now but maybe it’s still there, just a little bit.’

‘What do you do about it?’ asked Henry.

‘Oh, well,’ said Mum, swivelling round, ‘I don’t know. I think I just notice it and even make a little room for it. Maybe I even say, Ah, there you are! But I also remind myself that it’s not the whole story. That I’ve had very enjoyable holidays in the past and this one will likely be the same.’ She smiled and the wrinkles around her eyes fanned out.

‘Uh-huh,’ said Henry. ‘Okay. Right.’ The fluttery worry was suddenly still. He tapped his fingers against his chest and breathed in deeply. His mum turned back and dug out another barley sugar from the glove box.

‘Lolly, anyone?’

‘No, thanks,’ said Dad.

‘Yes, thanks,’ said Henry. His mum tossed it and he caught it first go. He snuck a sideways, hopeful glance. Ah gosh, Patch was asleep.

Henry opened the barley sugar slowly and popped it into his mouth. Before long, the edges of the lolly began to splinter. He pondered what his mum had said about making a little room for the worry. He imagined what it might look like. He was pretty sure if he had to draw it, it would be a big round grey tumbleweed of dust, with skinny black-and-white-striped legs poking out and red boots, with untied shoelaces. ‘Have a seat!’ Henry imagined himself saying to it, plumping up a cushion. ‘Would you like a glass of water?’ The idea made him want to laugh out loud.

Henry gazed at his mum. She was chomping on her barley sugar. It sounded like a cliff crashing inside her mouth. She wasn’t good at lolly-sucking competitions. She didn’t really have the patience. Henry was always winning those competitions. He was good at holding a lolly in his mouth until it was just a sliver.

His mum wasn’t so good at making

cakes and slices for fundraising days either. Or remembering school notes. But she was good at knowing things. Yes, his mum was good at knowing things inside him that he didn’t even have words for yet. There was something reassuring about that, like he was a trapeze artist in a circus, swinging through the sky, with the biggest, strongest safety net in the whole universe stretched out wide to catch him.

Henry crunched the last tiny sliver of barley sugar. He slid his head against the edge of Lulu’s rock hard booster seat, found one tiny comfy spot and went off to sleep.

ARRIVING

And then before Henry knew it, they were nearly there.

‘Woo-hooo!’ cried Dad. ‘Wakey-wakey, sleepyheads!’

Lulu woke with a start, her cheek damp with dribble. ‘How much longer?’

‘Five and a half hours,’ said Dad, with a laugh.

Mum turned her head. ‘Five minutes.’

Lulu pressed the button for her window. A breeze rushed in and her hair whirled about. Bellbirds pinged in the forest above them. ‘I can smell sea!’ she called, wiping her cheek.

Patch pushed the button for his window too. He leant his head out, his fringe lifting up like a salute. He sniffed. ‘I think you’re right,’ he said to Lulu.

And then, after they chugged up one last hill and around a bend, they could see it. Yelonga Inlet stretched out before them. Henry let out a slow, wonderstruck breath. There were more shades of blue than he could possibly count. Patches of turquoise. Splashes of kingfisher blue. Pools of sapphire, indigo and even navy.

‘Here comes the bridge,’ said Dad. Their car shuddered across, the trailer jolting behind them.

‘Is it a lifting bridge, Daddy?’ Lulu slid forward and gazed up.

‘It sure is,’ said Dad, glancing out at the water. ‘But the bridge only goes up when there’s a big boat wanting to get in or out. Ah, what a shame, low tide! I was hoping the water would be rushing in to greet us.’ He laughed. ‘I thought I’d get a kitesurf out front before dark.’ He turned to wink at Henry. ‘But maybe I’ll have to settle for a bike ride instead?’

A shivery jolt ran up Henry’s spine.

‘Ha-ha,’ said Mum. ‘Fat chance! We’re going to be too busy for that.’

The Grand, Genius Summer of Henry Hoobler

The Grand, Genius Summer of Henry Hoobler